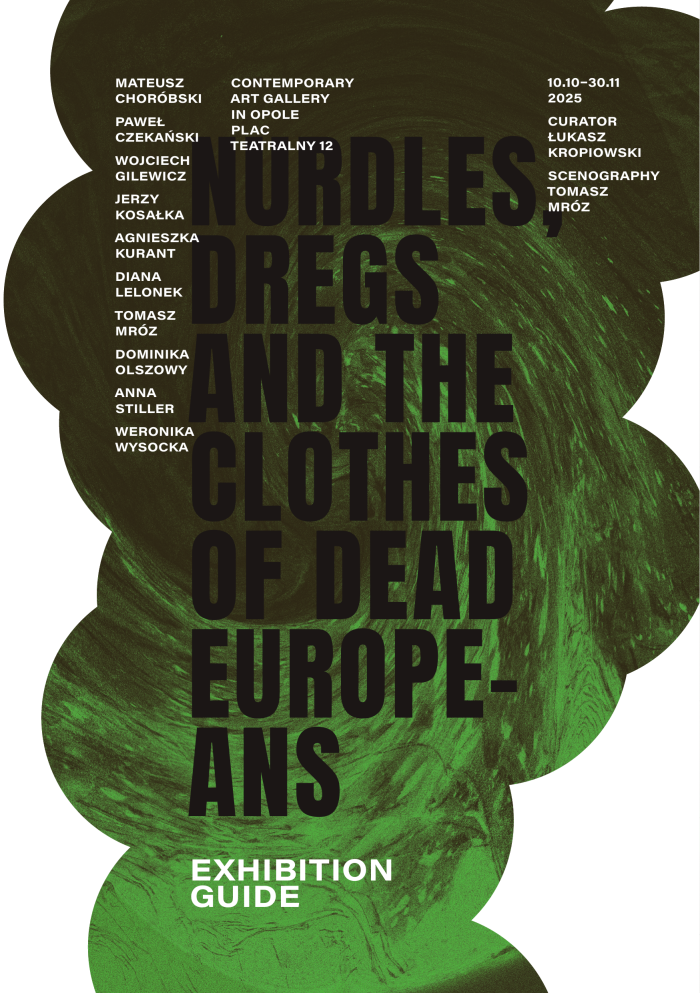

Nurdles, Dregs and the Clothes of Dead Europeans

The exhibition entitled Nurdles, Dregs and the Clothes of Dead Europeans

addresses the issue of waste in the broadest possible spectrum, while at

the same time providing a concise overview.

Artists

Mateusz Choróbski, Paweł Czekański, Wojciech Gilewicz, Jerzy Kosałka, Agnieszka Kurant, Diana Lelonek, Tomasz Mróz, Dominika Olszowy, Anna Stiller, Weronika Wysocka

Contemporary Art Gallery in Opole

Plac Teatralny 12, Opole, PL

Curator

Łukasz Kropiowski

Introduction…

1. The Great Wastrel

Leonia, one of Italo Calvino’s ‘invisible cities’, is a place whose wealth is measured not so much by the goods produced and purchased as by the rubbish disposed of[1]. The metropolis regenerates itself daily – every morning, residents surround themselves with foodstuffs covered in attractive packaging that attests to their freshness, the latest models of household appliances, the most fashionable clothing, and even new editions of encyclopaedias. And then, packed in plastic bags, the ‘remains of yesterday’s Leonia’ are transported outside the city. As the art of manufacturing continues to evolve, waste becomes less biodegradable and more durable. The remains of the previous day ‘pile up on top of the rubbish from the day before, and from all the earlier days, years and decades.’

This vision of civilisation as a centre of constant waste eruption captures the consumerist reality of ‘throwaway societies’ with such accuracy that the literary hyperbole imperceptibly becomes nothing more than an ever-so-slight exaggeration. It was on the streets of one of the thousands of “Leonias” around the world that Jean Baudrillard studied the ‘myths and structures’ of consumer society, concluding that products are no longer manufactured for their utility or quality, but for their ease of conversion into waste[2]. His research showed that production order is maintained only at the expense of the ‘calculated “suicide” of the mass of objects.’ This operation is based on ‘technological “sabotage” or organised obsolescence under the cover of fashion’.

On the streets of the city, the sociologist encountered ‘great wastrels’ — stars of disposability who provide a model and media stimulus for mass consumption (although its forms are becoming a parody of themselves — a chic outfit worn by a celebrity for one evening is transformed into affordable disposable underwear). It was also on the streets of one of Leonia’s sister cities that Zygmunt Bauman noticed the fate of renegades – outcasts who failed to follow the example of the wastrels in order to fulfil their duties as Leonians: “Since the criterion of purity is the ability to partake in the consumerist game, those left outside become a ‘problem’, the ‘dirt’ which needs to ‘disposed of.”[3] The opposite of the great wastrel is therefore the indolent consumer – a “flawed” citizen incapable of consuming quickly and disposing of their purchases equally fast. This is well exemplified by the removal of beggars from shopping centres, relegating them – just as the rubbish of Leonia – to the periphery beyond the central, commercially attractive parts of the city).

2. Nurdles, clothes of dead Europeans, dregs (The Moderate Wastrel)

The exhibition entitled Nurdles, Dregs and the Clothes of Dead Europeans addresses the issue of waste in the broadest possible spectrum, while at the same time providing a concise overview. The title outlines the thematic scope:

- Nurdles are small plastic pellets – granules used in the production of plastic items. They have been called ‘the worst toxic waste you’ve probably never heard of’[4]. They are produced in huge quantities, each shipment of this semi-finished product contains trillions of pieces. The nurdles in the title refer to the scale of the waste crisis and unprecedented overproduction.

- ‘Clothes of dead Europeans’ is the colloquial name used by the people of Ghana and Tanzania who sell second-hand clothing that arrives in Africa from Europe[5]. They are puzzled by the fact that clothes in good condition are thrown away. The term refers to the issue of hyper-consumption, its habits and standards (fast fashion, planned obsolescence) and ‘toxic colonialism’, i.e. the transfer of waste from the Global North to poorer regions of the world. On the other hand, second-hand clothing is also a symbol of all practices aimed at reducing the generation of waste (freeganism, freecycling, reuse, upcycling).

- Dregs are a symbol of all kinds of impurities that we fight against on a daily basis, but in which we are doomed to failure in the long run. They represent everything that inevitably accumulates, gathers and piles up around us: leftovers on the sink strainer, dust on furniture, cobwebs in room corners, junk in drawers, hair in the shower drain, plaque on teeth, dirt under the fingernails, lint in the belly button. This is a less global, more individual, personal, and often even intimate aspect of waste.

The waste generated by the modern economy and by every citizen of a consumer society is long-lasting and ubiquitous. Waste can rightly be considered an inevitable by-product of almost every human activity since the dawn of our species. However, we must be aware of the current intensity of its production. We live in an era of ‘great acceleration’ – in just the first two decades of the 21st century, humanity has already used up 40 per cent of the total energy consumed in the entire history of civilisation. It is estimated that global waste production amounts to over two billion tonnes of solid waste and tens of billions of tonnes of industrial waste annually. The waste accumulates not only in rubbish bins, landfills and dumps, but also in the soil, water and air. Litter on the slopes of eight-thousanders, new ‘geological’ formations such as plastiglomerate and technofossils, plastic bags in ocean trenches, a huge garbage island in the Pacific Ocean (and the beginnings of an eighth continent called the Plastisphere), microplastics in the blood and tissues of living organisms, hundreds of millions of particles of debris in Earth’s orbit, and debris left on the Moon by the Apollo mission participants – these are some of the most spectacular “achievements” in the field of modern littering. The global economic system based on continuous exploitation and shifting the costs of development onto nature – regarded on the one hand as a gift box, and on the other as an infinitely capacious rubbish bin – as well as the incessant festival of disposability, whose attractions include the luxury of unrestricted disposal, blurring the line between packaging and product, and producing “instant waste” often used to get rid of other waste (rubbish bags, poop bags, dust cloths, paper towels) – all this makes the problem of waste grow to grotesque proportions and become insurmountable. In the face of advancing pollution, Peter Sloterdijk wrote about creating a planetary ‘ecological community of interest’ from which a ‘new, far-sighted’ culture could emerge[6]. This culture would have to influence our consumer habits and economic practices, and ultimately replace the model of the great wastrel – if not with a savings superstar, then at least with a more moderate wastrel who thinks more often about durability, recycling and reusing objects.

[1] I. Calvino, Invisible Cities, transl. Wiliam Weaver, Harcourt, 1974, pp.86-89.

[2] J. Baudrillard, The Consumer Society: Myths and Structures, transl. George Ritzer, London, 1998, pp. 40-43.

[3] Z. Bauman, Postmodernity and Its Discontents, (trans. L. Davis), Cambridge, 1997, p. 15.

[4] Oliver Franklin-Wallis, Wasteland: The Secret World of Waste and the Urgent Search for a Cleaner Future, London 2023, p. 78.

[5] Ibidem, p. 137.

[6] P. Sloterdijk, A Crystal Palace (in: In the World Interior of Capital); transl. Wieland Hoban, Kryształowy pałac, Cambridge, 2013, p. 186.